Being The “Good” Immigrant Won’t Save You From Racism: An Open Letter to My Cabo Verdean Community

Black Lives Matter Protest in New York City.

Photo Credit: Paulo Silva, Filmmaker. View entire collection at unsplash.com/@onevagabond.

The current racial climate in the US has created ripple effects throughout the world, inspiring other Black communities to take to the streets demanding their rights as human beings, to exist and thrive.

It has also reignited debates within the Cabo Verdean community about our understanding of identity and being “good” immigrants. As a US-based Cabo Verdean scholar, I argue that Cabo Verdean immigrants in the United States have a responsibility as African immigrants (yes, we are Africans) to learn about Black history in the context of the United States, to understand the struggles and respond in solidarity with the Black American community whose history is also ours. If one looks at Cabo Verde’s population, culture and ethnic make-up as well as political and economic affiliations, we are Africans. To think that being a “good immigrant,” that is to work hard, not go to jail, stay silent on political matters, and not demand our rights as human beings, somehow shields us from experiencing racism and other forms of discrimination is naive. For some Cabo Verdeans, being of lighter skin and having fine, curly hair might have saved us back in the day but it won’t today. In fact, separating ourselves from the Black American community is divisive and it is a harsh denial of our rich African identity and history. In her work, Cabo Verdean professor and historian, Dr. Aminah Fenandes Pilgrim, discusses how interwoven Cabo Verdean and Black American identities have been and the importance of this relationship in civil rights and independence movements in the United States and Cabo Verde. She says, “if we are to track a chronology of the ideology and identity politics of "black" people and blackness, that accounting would be incomplete without the role of Cabral and Cape Verdeans in the US who have contributed to every American war since independence, every pivotal national struggle such as the 195o's-196o's Civil Rights Movement, and to African-American popular culture (think of the recently deceased Horace Silver, considered one of the greatest Jazz musicians). To fully appreciate Cape Verdean American history, it is necessary to engage with black or African-American history as this is the community to which we have most often been associated (even when we have chosen not to identify as such).” We can point to the history of discrimination faced by Cabo Verdeans at the hands of both whites and Blacks in the United States, when we first established communities in the late 1800s and early 1900s as well as more recent experiences to explain why many of us have decided to stay to ourselves and not associate with other communities. However, I argue that it is time for us to take the lead and move forward in solidarity with the Black American community.

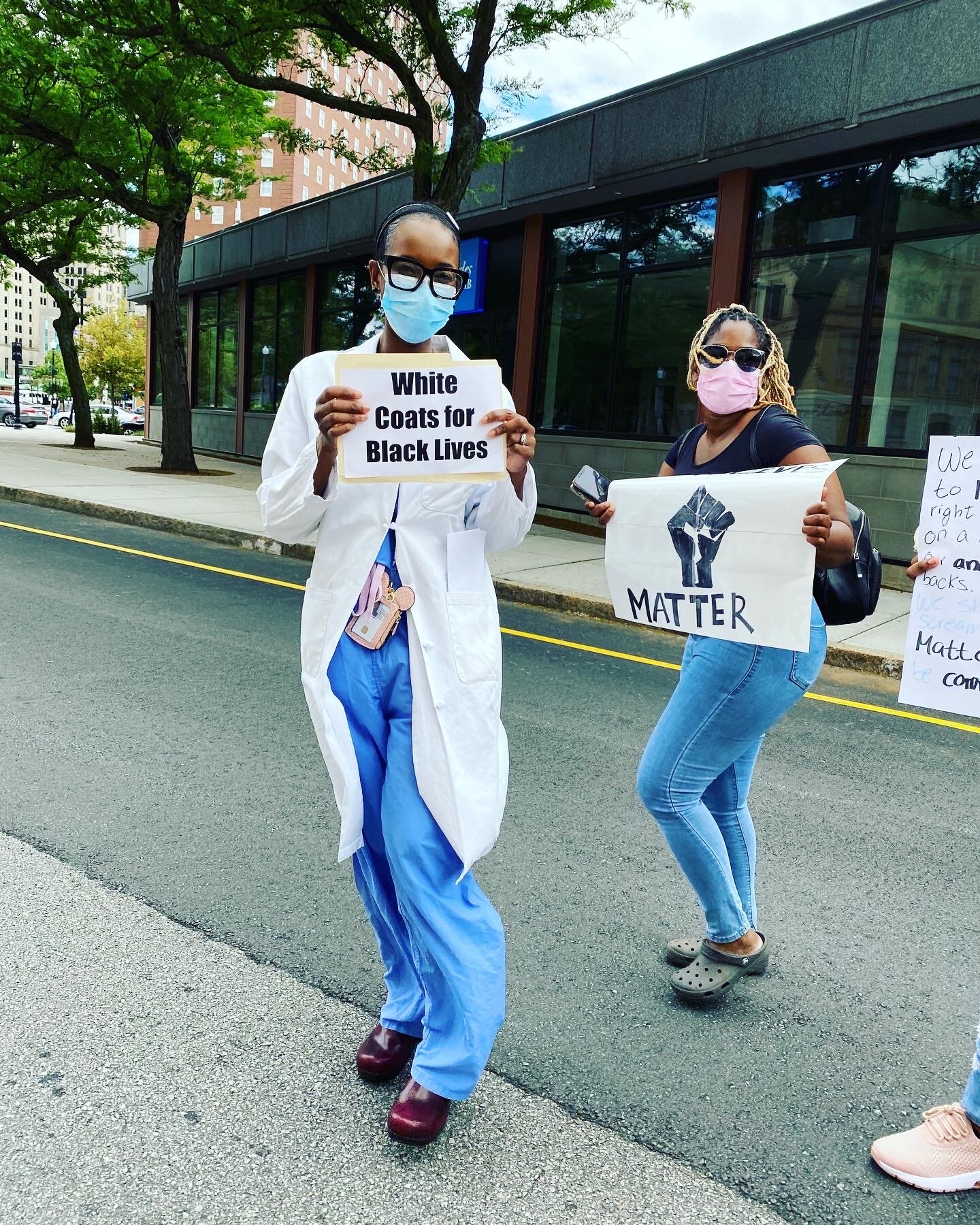

Cardiovascular Physician, Dr. Carla Moreira (Left) and Dental Hygienist, Miryam Mendes-Job (Right) Protesting at the Gen Z and Code Black march in Providence, RI , June 14, 2020.

I will not argue whether or not we are Black, African or Cabo Verdean because that is not my objective in this essay. We can certainly be all of these identities as they don’t have to cancel each other out. There is existing published research that speak to our identity as Africans and Blacks. I have included publications at the end of this article which speak to that. However, I do invite us to ask ourselves, “why do we choose one identity over another? Is this decision intentional? And, what is the intention behind that decision”?

My goals here are 1) to spark conversations around our experiences as African immigrants in the United States and recognize how systemic racism and discrimination may have impacted our lives and 2) to address the ways we have informally or formally distanced ourselves from the Black community and the responsibility we, as a Cabo Verdean community have towards the Black American community to learn about its history and become better allies and 3) equip us with selected resources in English and Portuguese to help spark learning and discussions in our homes and community.

The current racial climate is not about our individual experiences. This is about understanding a racist system that was put in place to systemically oppress Black families and how it still prevails today. We can no longer afford to hide behind our seemingly complex ethnic identity, language barriers and long working hours as an excuse to not be informed and be better allies. It is time to accept and celebrate our Black African identity and all that this entails. We may want to say the answer to all of society’s ills is to love and be kind to one another, but this is rather dismissive to communities of color that have experienced institutional racism and discrimination. So, the answer may be love and kindness but there is absolutely nothing wrong with also demanding drastic changes in American institutions to ensure all people are afforded access to equal rights. Similarly, when we make comments like, “I don’t see color” and “I love all people, regardless of color,” we are dismissing the unique identity of each person and denying the fact that some communities face racism and discrimination.

My views about what it meant to be Black in the world were based on what was fed to me and not what I took the responsibility to learn for myself. Growing up in Cabo Verde, Hollywood informed me that except for Michael Jackson, Eddy Murphy, Whitney Houston, and Diana Ross, Black people in the US were poor and dangerous. Because of their shared colonial past and language, Brazilian novelas (soap operas) occupied most televisions in Cabo Verde. The novelas also portrayed Black people as slaves and domestic workers. However, keep in mind the same white-dominated media I described above fed Black people in the United States and people all over the world stereotypical images and narratives of Africans as “booty scratchers” and “hungry, famished and barefoot.” Some of us may have been hurt by these comments coming from everyone including Black Americans. In this light, it may not be productive to engage in “oppression Olympics”, that is to argue who has been more hurt or oppressed. This should be a time to move forward collectively, with the knowledge that as Black people we have all been oppressed by systemic racism and it is time for change.

It wasn’t until I arrived in the United States that I realized I was Black. Not that I wasn’t Black before but being from Cabo Verde our racial identity is not centered in everyday discussions as it is in the United States. I spent my high school years at a predominantly white, all-girls private school, where we learned about selected Black Americans but not in a way that centered stories of Blackness in everyday life, experiencing joy and sorrow. I also didn’t relate because my experiences as a Cabo Verdean were not centered in a history of slavery. I would later understand that although the experiences may have not been the same, Cabo Verdeans also endured a colonial past rooted in racism and socio-economic discrimination at the hands of the Portuguese state. Let’s not forget the drought and famine of the 1940s, where half of the Cabo Verdean population died, while the Portuguese colonizers did nothing to help.

Thanks to my education at a Historically Black University and personal interactions, I understand what it means to be Black in this country and for the most part, can identify racism and discrimination when I see it. I remember one incident that happened when I accompanied my mother to a doctor’s appointment at the local community clinic. My mom was trying to explain to the doctor, a white male, that she didn’t take the medication he had previously prescribed because she experienced strong side effects. Because she didn’t feel fully comfortable speaking English, I was my mom’s interpreter, something that many immigrants children can relate to. When I explained it to the doctor, he became visibly upset and said, “if she’s not going to follow my orders and not take the medication then this is not going to work.” My mom was upset and felt ashamed as if she did something wrong in exercising her right to ask for better healthcare. We walked out of the room towards the lobby but I turned around because I felt a need to speak up for my mom. I told the doctor about how rude he had been to my mother, how she knows her body and health needs and that he should work on improving his bedside manners if he planned to be a physician in immigrant communities of color. From that moment on, my sisters and I, committed ourselves to accompanying our parents to their healthcare appointments because we understood at any point they could be discriminated against solely based on their ethnic background and limited English language skills. As you read this, think about the ways you or a family member may relate to these types of racist and discriminatory incidents. How many times have you felt “some kind” of way at the doctors’ office or at a parent/teacher meeting because white folks were irritated with you or your family because of your accent? How many times have white folks looked at your Cabo Verdean food in disgust or told you to put your loud Cabo Verdean music down? Were you or your family able to recognize these or similar moments as racism?

Because of these experiences I decided that my life and career would be centered on social justice work for Black African communities, particularly women and girls. By no means, am I sharing my educational background to brag about how educated I am. I mention it to prove the point that US school systems are failing all our students, regardless of color by not teaching them the realities of Black history and experiences at early stages in their academic journey. Beyond Black History Month featuring a few well known figures like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., school systems deny our children their alienable right to a diverse education. We have a right to be taught the true impact of slavery on society in general, and on Black lives, in particular, to have a full appreciation of today’s racial climate.

I have learned the reality of being Black in the United States. Africans were taken from their lands, even from Cabo Verde, stacked on ships like animals and brought to the United States, Brazil and the Caribbean. They endured over 400 years of slavery. They worked in plantations in southern parts of the United States, from sun up to sun down for no pay as property of slave owners. In the north, they worked the textile industries just like Cabo Verdeans did during the industrial period, living in deplorable conditions. The women bore children who were bought and sold like goods. Enslaved Africans were beaten and killed. They were property. Even after slavery ended, there were still laws that prevented Black Americans from being free, owning property and voting. There were organizations like the Ku Klux Klan that terrorized Black people by burning their homes, lynching and beating them to death. Some of the members of the KKK were part of the police forces and elected politicians. In 2020, the KKK is still operating in the streets of this country and endorsed the presidency of Donald Trump. This is important in understanding why the Black community does not trust law enforcement agencies.

150 years after the abolishment of slavery, Black Americans still experience systemic racism. When I say systemic racism, I am specifically talking about the practices of discrimination by social and political institutions based on someone’s race and skin color. The facts show that there are significant differences between whites and Blacks in the United States, in accessing education, homeownership, generational wealth, health, employment, justice in the criminal system, housing, and political power. In fact, the wealth gap between whites and Blacks has not changed since the 1960s, the era of the Civil Rights Movement, Blacks are 2.5 times more likely to be stopped and arrested by the police than whites, and even after obtaining a college education, Blacks earn 3 times less money than whites. Even during this pandemic, Blacks have been impacted by Covid19 at higher rates than whites, due to lack of access to adequate healthcare. We cannot say, “if only Black people didn’t commit crimes” or “If only Black people worked harder or studied harder, they too could make it.” The above facts show us that something bigger and more systemic is going on and it must be end.

Lauraberth Lima protesting at the Brooklyn Liberation march for Black Trans Lives, June 14, 2020.

Photo credit: Ariela Rothstein

The Black American community has a right to be angry. The same system that existed since the period of slavery is still existent today and continues to uphold the barriers for the advancement of Black people in this country. Law enforcement agencies still discriminate against Black citizens. The difference is the advancement of technology and social media have made it possible for every day citizens to document events and quickly share information, such as the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland and hundreds of others. As many have said, things are not getting worst, they’re getting filmed.

When we see people on the streets protesting, destroying and looting property, I want us to think critically about this history of over 400 years of free labor to build this country and violence towards the Black community by a system controlled by whites. An economic system that was legally set up to use Black people as property and later, prevented Black communities from owning property and families from becoming financially stable, sometimes driving them to illegal economic activities for survival. The destruction of property and looting you see on the streets is not a random act. It is done intentionally to protest an economic system that used free Black labor to build wealth for whites and left the Black community in destitute conditions until this day. In the eyes of the Black community that property doesn’t belong to the Black community. Even for Black owned businesses, they are most likely paying banks higher interest rates than their white counterparts, for the business loans they were given. By no means am I asking you to destroy and loot property. However, when you see Black people protesting, destroying and looting property, please try to understand that their actions are not random and that there are different forms of protest which we may or may not agree with.

The Black community in the United States does not want to be told what to do anymore. Many of us, proud to be Black and Cabo Verdean, have taken to the streets with our brothers and sisters, demanding justice and an end to systemic racism and white supremacy in the US and the world. The time is now for all of us to be “ the good immigrants” and stand on the right side of history.

What Are Some Steps We Can Take to do Better?

1. Hold the Cabo Verdean government accountable in actively engaging leaders in the Black communities in the US to form partnerships for investment and development instead of always looking to Europe for “help”. Black Americans want to invest in businesses and visit African countries to participate in historical/cultural tourism. They have been going to Ghana and Senegal, etc. They should be going to Cabo Verde as well and spending their money there.

2. We can individually educate ourselves about the history of Blacks in the United States from the Black perspective and Cabo Verde’s history of colonialism and systemic racism. In this history, you will find similarities and solidarity.

3. Understand the difference between systemic racism and prejudice. Black people and people of color cannot be racists. Racism is based on power and the ability to impact someone’s life in a way that prevents them from accessing social, political and economic resources. Blacks can be prejudice against other groups but we have never had enough power to impact any community’s access to resources.

4. Being a “good” or “model” immigrant, who always works hard and stays away from trouble won’t prevent you from experiencing racism and discrimination. Just because you think you haven’t experienced racism doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened to you and it doesn’t happen to others. Systemic racism is not about individual experiences of discrimination, but rather institutional barriers that keep Black people as a group from accessing all their rights in society.

5. Black Lives Matter doesn’t mean that other lives don’t matter. This movement is specifically demanding that Black people have equal access to political, social and economic rights as whites and other groups.

6. This is not about your friend who is a good, kind white police officer. This is about law enforcement agencies in general and their racist practices. Your white police officer friend should want to reform a system that has discriminated against Blacks. If they don’t, then they are also part of the problem.

Books and Articles About Cabo Verdeans in the United States and History of Cabo Verde

The Cape Verde Islands: from Slavery to Modern Times by Elisa Andrade

D’Nos Manera: Gender, Collective Identity and Leadership in the Cape Verdean Community In the United States by Terza Lima-Neves, https://vc.bridgew.edu/jcvs/vol1/iss1/6/

Free Men Name Themselves by Aminah Fernandes Pilgrim, https://vc.bridgew.edu/jcvs/vol1/iss1/8/

Between Race and Ethnicity: Cape Verdean American Immigrants, 1860-1965 by Marylin Halter

Films about Black history (some have Portuguese subtitles)

https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/two-thumbs-up/

Some Articles in Portuguese You Can Share with Your Families:

Ta-Nehisi Coates: https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/colaborador/ta-nehisi-coates/

As Raizes Negra Da Liberdade por Nikole H. Jones

https://www.revistaserrote.com.br/2020/03/as-raizes-negras-da-liberdade-por-nikole-hannah-jones/

A Quarentena Interminavel do Racismo por Brandi T. Summers

https://www.revistaserrote.com.br/2020/05/a-quarentena-interminavel-do-racismo-por-brandi-t-summers/

A Face Animal da Brutalidade Racista por Helio Menezes

https://www.revistaserrote.com.br/2020/06/a-face-animal-da-brutalidade-racista-por-helio-menezes/

Links da Quarentena Um Manifesto de Spike Lee e o Debate Sobre Racismo

Black Lives Matter Protest in New York City.

Photo Credit: Paulo Silva, Filmmaker. View entire collection at unsplash.com/@onevagabond.